100 is enough

Interview with Tyler Brown on his new tabletop game

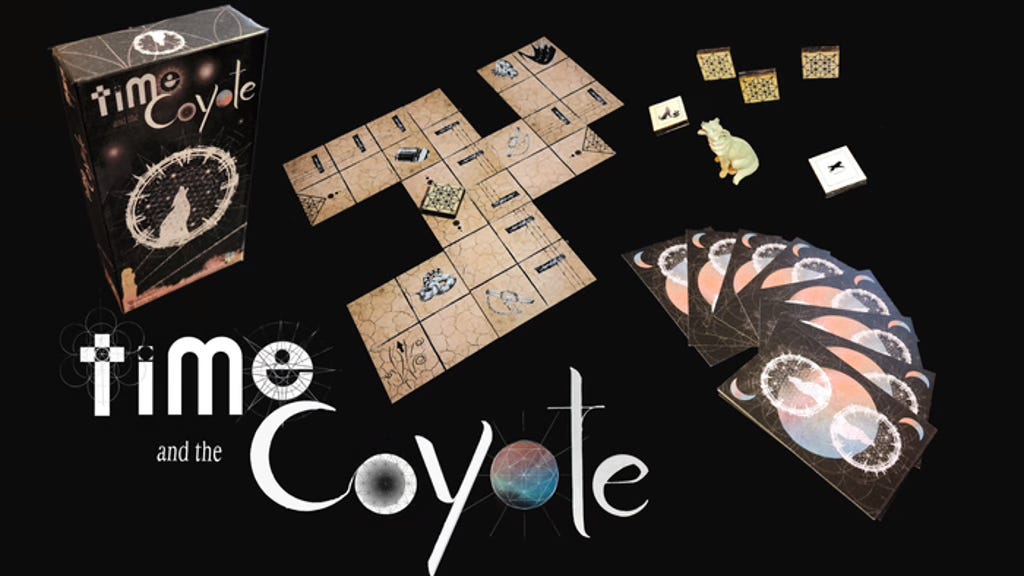

Today I’m talking to Tyler Brown, the designer of Time and the Coyote which has just over 48 hours left on kickstarter, so go check it out now.

Tyler is making this game as part of the Make 100 format for Kickstarter. Essentially, you just make 100 of something, anything! And I think it’s a fantastic way to create a really personal piece of art for a very specific crowd. I think more people should do it. Sometimes, crowdfunding really is just about making something beautiful exist where nothing existed before, rather than using it as a digital slot machine that you hope will propel you into financial security (you know, how I use it). Time and the Coyote is beautiful, super fun, and the development story is fascinating as well. Check out what Tyler has to say below.

Sean: So, I just love the Make 100 format for Kickstarter. I think for KS its a good way to entice new creators to dip their toes into crowdfunding, but even for creators I think it’s a cool way to think about a project. I’m going to Make 100 of this thing and then it’s gonna be done. It’s more bespoke, it’s not scalable, and that sort of limited aspect really appeals to me. I’ve recently gotten a Make 100 mug for my wife, Lindsay, from Kickstarter. What drew you to doing this project as a Make 100 project rather than something more open ended?

Tyler: I think the simplicity and control is what drew me to do a Make 100 campaign. I have so many prototypes and am always struggling to mold them into things that could be sold or brought to market by publishers and at the same time keep them genuinely my own. My first experience with signing a game with a big publisher was eye opening. Overall it was a good experience and I’m happy with the product, but the back and forth, asking for permissions, and general anxiety of conflict was tough on my brain and what I wanted to bring into the world.

Really, I think most creative endeavors are about finding a balance between knowing that art by committee is generally shit but also knowing that iron sharpens iron. With Time and the Coyote, I knew the game was small enough for me to handle on my own and it’s such a personal game to me that I didn’t want the kind of feedback or pressure a publisher may have brought to it. I knew I could easily produce 100 copies, and the limited aspect of it would help heighten the poetic nature I had in mind for the design, which I hoped would shine through.

Sean: Yeah, I agree completely. There’s a huge value to creative collaboration, but those relationships take time to build and involve a lot of vulnerability and sometimes pain! I think it also takes time to build up your voice until it’s strong enough to sing on it’s own, then you can bring in different harmonies, build up other voices, as long as you know that yours won’t get lost in the choir. So what about this project felt personal to you?

Tyler: Yeah, collaboration can definitely be tricky.

It might sound a bit sentimental, but the game turned into a way for me to connect with my dad. Time and the Coyote was initially inspired by a book called Coyote America: A Natural and Supernatural History, but the theme of the game came from growing up in Wyoming with my family.

My dad was a government trapper in the 80s and early 90s and I grew up surrounded by coyotes—our garage was always filled with coyote skins, traps, and rank scents used to lure them, made from beaver castor, coyote urine, skunk entrails, etc. We even had a pack of coyote pups as pets that he had found after he had trapped their mother (I feel I should add that he stopped trapping/hunting about 20 years ago and traded his gun in for a camera. He sort of detests the thought of killing anything now, and has instead been working to share the beauty of nature as a professional photographer).

My brother and I used to go out with my dad to walk his traplines or to call coyotes, and while my brother really enjoyed it and grew into more of a hunter and fisherman, I was the opposite. I spent a lot of the time sitting in the truck reading a book or playing my gameboy. We grew up with different relationships with our parents and I always felt like there was a wall up between me and my dad, even though I was always mentally intrigued by his work.

So, long story short, the game started with coyotes because I wanted to make a game that would connect to my dad. The abstract nature of the game let me tell a story of nature and myth in a way that echoed what I feel toward my dad. I get emotional thinking of the game because it's my way of saying that even though I sort of didn't like the process of wandering around in the freezing Wyoming wind and hunting or trapping coyotes, I still felt very close to him when I was included. Making this game is a way to express that to him.

Sean: Has he played the game? What does he think about it?

Tyler: Unfortunately, he’s not much of a gamer. I only get to see my family every few months or so for holidays and we tend to play lighter party style games when we get to play. Designing the game gave me the opportunity to chat with him about it and his experience with coyotes. He recommended a handful of books for me to read about coyote myths and trapping, so I know he’s intrigued by the game. My brother has also used a number of my dad’s photographs when creating the icons for the game, so it’s definitely a family effort. I think my dad will appreciate the game once he gets a final version in his hands.

Sean: I think that’s cool, all of you approaching this topic with your different lenses, and connecting in that way. What did you glean from your research about coyotes and how does that come through in the game? In fact, what is the game even about?

Tyler: The game is a 2-player asymmetric game where one player plays the Coyote and the other is Time. It’s an abstract game where each player is trying to control the most Places of Power. That’s the basic concept. To go into the research and how the theme comes to life throughout play will need a bit more of an explanation.

Most, if not all, dogs or canids originated and evolved from North America about five million years ago and then wandered off to the rest of the world, except the coyote which remained. I think the question of why it never left is intriguing. Combine that with its survival through the last ice, when many other canids and predators went extinct, speaks to its versatility as a species.

Then when you consider the mythology that has grown around coyotes, I think they become somewhat magical, which I have tried to add to the gameplay. The origin of Coyote as a trickster and storyteller came from the Aztec god Huēhuehcoyōtl and there are endless stories from nearly every Native tribe in North America. There are stories of Coyote as creator, as fire-giving, of Coyote creating the stars, resurrecting the dead, even inventing the vagina. Essentially, this strange “prairie wolf,” as Lewis and Clark referred to it when they first discovered it, is responsible for everything. And when people saw them and watched them, they acted so much like people—living in families, tending to mate for life, adapting fission-fusion responses just like humans—we were kind of looking into a strange mirror. Then eventually we started passing laws to decimate them, strangely calling them Bolsheviks, essentially trying to exterminate them, and what did they do? They survived even harder. This is what I wanted to make a game about—the coyotes survival in the face of persecution.

In the game, the Coyote uses six Instincts to survive the onslaught of Time. The instincts either try to tell about their survival techniques or their mythology and magical aspects. For instance, the Howl Instinct allows the Coyote to draw cards. In nature, when a coyote howls, they are essentially doing roll calls or a census and adjust their populations accordingly. If they do not hear many responses to their howl, the size of their litters increases and they have more pups. In the game, if Coyote cannot find respite because Time has destroyed all their Dens, the Coyote can use the Howl Instinct and draw more cards in order to search for more Dens to play. The same goes with their Overcome Instinct: Time creates a landscape of cards that the Coyote must be able to traverse or else they’ll lose and the Overcome Instinct simply allows the coyote to skip over spaces. This is similar to how coyotes have learned traffic patterns and will find intersections with stop lights in order to move across or they can simply read traffic well enough to know when it is safe to cross. Coyotes have grown accustomed to the progress of humankind and have evolved along with us.

Sean: Holy shit. This is so incredible. I didn’t know any of this stuff. I mostly think of Johnny Cash on the Simpsons when I think of coyotes. This is really fascinating stuff and I love how you’ve incorporated it into the gameplay. I’m a real sucker for densely thematic, super tight games. Particularly if they’re micro games a la Seiji Kanai, or rules lite RPGs like Chris McDowall’s Into the Odd. I’m a struggling uh minimalist by nature, and the craft of paring things down to what’s essential is always really fascinating to me. I also just love all the research that went into this, the game should come with a bibliography. Was there any work in particular that stood out to you when you were developing the game?

Tyler: I totally agree about minimalistic design tendencies, I love them. But I think I may be a maximalist designer at heart. I don’t know about you, but whenever I research something I have a compulsion to consume EVERYTHING and then want to make sure everyone knows it all. Game design isn’t necessarily the best medium for that kind of information exchange though. Luckily, I have enough people around me to reign me in, and for Time and the Coyote it worked out. The pages of notes I took to make a war/strategic Euro game eventually just got tossed and boiled down into the poetic little abstract game it is today.

A few that really stood out and I can recommend are:

As I mentioned previously, Coyote America: A Natural and Supernatural History by Dan Flores is the most comprehensive book on the topic. It spans the ecological to the mythological, but can get pretty dry in places.

There’s a coffee table type book called Seasons of the Coyote, edited by Philip L. Harrison, which has a number of interesting essays and personal accounts with coyotes and some pretty incredible accompanying photography.

Though it is almost impossible to find and somewhat technical, Bloody Tracks on the Mountain Where the Wild Winds Blow, by Charles Alma Wilson recalls his experience trapping coyotes throughout his life and the brutal means that were introduced to exterminate the species.

Then for Indigenous Coyote tales, I’d recommend a little collection called Giving Birth to Thunder, Sleeping With His Daughter: Coyote Builds North America edited by Barry Lopez, I’ve been reading this one aloud to my wife lately and we are loving how wild the stories can get, there’s almost a strange Winnie the Pooh like innocence to it.

There’s also a great documentary that came out in 2023 and though I had watched it after the game was nearly done, it is well worth the watch—it’s called American Bolshevik, directed by Julie Marron.

Sean: Thanks for talking to me, Tyler. For everyone else, I hope you think about making something beautiful for a specific audience. We’re going to dive more into what that looks like next time.

Links

Kickstarter: http://kck.st/3DYrGlu

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/tbrown1079/

For inquiries on getting the game outside the USA, email: prufrockstudios@gmail.com